Disneysaurus (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tag: sourceedit |

Disneysaurus (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tag: sourceedit |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

[[Image:Theropodscalewithhuman.png|thumb|right|200px|Size comparison of selected giant theropod dinosaurs, with ''Tyrannosaurus'' in purple.]] |

[[Image:Theropodscalewithhuman.png|thumb|right|200px|Size comparison of selected giant theropod dinosaurs, with ''Tyrannosaurus'' in purple.]] |

||

''Tyrannosaurus rex'' was one of the largest land carnivores of all time; the largest complete specimen, [[wikipedia:Field Museum of Natural History|FMNH]] PR2081 ("[[wikipedia:Sue (dinosaur)|Sue]]"), measured 12.8 metres (42 ft) long, and was 4.0 metres (13 ft) tall at the hips.<ref name=SueFMNH>[http://www.fieldmuseum.org/sue/about_vital.asp Sue's vital statistics] Sue at the Field Museum. [[Wikipedia:Field Museum of Natural History|Field Museum of Natural History.]]</ref> Mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from more than 7.2 metric tons (7.9 short tons),<ref name=henderson1999>Henderson, DM, 1999. ''Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing'', from the Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 25, issue 1, pp. 88–106 [http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/25/1/88].</ref> to less than 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons),<ref name=andersonetal1985>Anderson, JF and Hall-Martin AJ, [[wikipedia:Dale Russell|Russell, Dale A.]] 1985. ''Long bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Zoology, vol. 207, issue 1, pp. 53–61.</ref><ref name=bakker1986>Bakker, Robert T., 1986. ''The Dinosaur Heresies''. New York, Kensington Publishing, ISBN 0-688-04287-2</ref> with most modern estimates ranging between 5.4 and 6.8 metric tons (6.0 and 7.5 short tons).<ref name=farlowetal1995>Farlow, James O., Smith MB, & Robinson, JM, 1995. Body mass, bone "strength indicator", and cursorial potential of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 15, issue 4, pp. 713–725. [http://www.vertpaleo.org/publications/jvp/15-713-725.cfm]</ref><ref name=seebacher2001>Seebacher, Frank. 2001. ''A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 21, issue 1, pp. 51–60.</ref><ref name=christiansenfarina2004>Christiansen, Per & Fariña, Richard A., 2004. ''Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Historical Biology, vol. 16, issues 2-4, pp. 85–92.</ref><ref name=ericksonetal2004>Erickson, Gregory M., Makovicky, Peter J.; [[wikipedia:Phil Currie|Currie, Philip J.]]; Norell, Mark A.; Yerby, Scott A.; & Brochu, Christopher A. 2004. ''Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Nature, vol. 430, issue 7001, pp. 772–775.</ref> Although ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' was larger than the well known Jurassic theropod ''[[Allosaurus]]'', it was slightly smaller than Cretaceous carnivores ''[[Spinosaurus]]'' and ''[[Giganotosaurus]]''.<ref name=dalsassoetal2005>dal Sasso, Cristiano and Maganuco, Simone; Buffetaut, Eric; & Mendez, Marcos A. 2005. New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod ''Spinosaurus'', with remarks on its sizes and affinities, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol. 25, issue 4, pp. 888–896. [http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1671%2F0272-4634%282005%29025%5B0888%3ANIOTSO%5D2.0.CO%3B2]</ref><ref name=calvocoria1998>Calvo, Jorge O., and Rodolfo Coria, 1998, December. New specimen of ''Giganotosaurus carolinii'' (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the as the largest theropod ever found, from the Journal of Gaia Revista de Geociências, vol. 15, pp. 117–122. [http://www.mnhn.ul.pt/geologia/gaia/7.pdf]</ref> |

''Tyrannosaurus rex'' was one of the largest land carnivores of all time; the largest complete specimen, [[wikipedia:Field Museum of Natural History|FMNH]] PR2081 ("[[wikipedia:Sue (dinosaur)|Sue]]"), measured 12.8 metres (42 ft) long, and was 4.0 metres (13 ft) tall at the hips.<ref name=SueFMNH>[http://www.fieldmuseum.org/sue/about_vital.asp Sue's vital statistics] Sue at the Field Museum. [[Wikipedia:Field Museum of Natural History|Field Museum of Natural History.]]</ref> Mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from more than 7.2 metric tons (7.9 short tons),<ref name=henderson1999>Henderson, DM, 1999. ''Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing'', from the Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 25, issue 1, pp. 88–106 [http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/25/1/88].</ref> to less than 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons),<ref name=andersonetal1985>Anderson, JF and Hall-Martin AJ, [[wikipedia:Dale Russell|Russell, Dale A.]] 1985. ''Long bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Zoology, vol. 207, issue 1, pp. 53–61.</ref><ref name=bakker1986>Bakker, Robert T., 1986. ''The Dinosaur Heresies''. New York, Kensington Publishing, ISBN 0-688-04287-2</ref> with most modern estimates ranging between 5.4 and 6.8 metric tons (6.0 and 7.5 short tons).<ref name=farlowetal1995>Farlow, James O., Smith MB, & Robinson, JM, 1995. Body mass, bone "strength indicator", and cursorial potential of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 15, issue 4, pp. 713–725. [http://www.vertpaleo.org/publications/jvp/15-713-725.cfm]</ref><ref name=seebacher2001>Seebacher, Frank. 2001. ''A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 21, issue 1, pp. 51–60.</ref><ref name=christiansenfarina2004>Christiansen, Per & Fariña, Richard A., 2004. ''Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Historical Biology, vol. 16, issues 2-4, pp. 85–92.</ref><ref name=ericksonetal2004>Erickson, Gregory M., Makovicky, Peter J.; [[wikipedia:Phil Currie|Currie, Philip J.]]; Norell, Mark A.; Yerby, Scott A.; & Brochu, Christopher A. 2004. ''Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Nature, vol. 430, issue 7001, pp. 772–775.</ref> Although ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' was larger than the well known Jurassic theropod ''[[Allosaurus]]'', it was slightly smaller than Cretaceous carnivores ''[[Spinosaurus]]'' and ''[[Giganotosaurus]]''.<ref name=dalsassoetal2005>dal Sasso, Cristiano and Maganuco, Simone; Buffetaut, Eric; & Mendez, Marcos A. 2005. New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod ''Spinosaurus'', with remarks on its sizes and affinities, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol. 25, issue 4, pp. 888–896. [http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1671%2F0272-4634%282005%29025%5B0888%3ANIOTSO%5D2.0.CO%3B2]</ref><ref name=calvocoria1998>Calvo, Jorge O., and Rodolfo Coria, 1998, December. New specimen of ''Giganotosaurus carolinii'' (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the as the largest theropod ever found, from the Journal of Gaia Revista de Geociências, vol. 15, pp. 117–122. [http://www.mnhn.ul.pt/geologia/gaia/7.pdf]</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | The neck of ''T. rex'' formed a natural S-shaped curve like that of other theropods, but was short and muscular to support the massive head. The forelimbs were long thought to bear only two digits, but there is an unpublished report of a third, vestigial digit in one specimen.<ref name=quinlanetal2007/> In contrast the hind limbs were among the longest in proportion to body size of any theropod. The tail was heavy and long, sometimes containing over forty vertebrae, in order to balance the massive head and torso. To compensate for the immense bulk of the animal, many bones throughout the skeleton were hollow, reducing its weight without significant loss of strength.<ref name="brochu2003"/> |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Tyrannosaurus.gif|thumb|258px]]The largest known ''T. rex'' skulls measure up to 5 feet (1.5 m) in length.<ref>[http://www.montana.edu/cpa/news/nwview.php?article=3607 Museum unveils world's largest T-rex skull] (2006-04-07) Montana State University.</ref> Large ''fenestrae'' (openings) in the skull reduced weight and provided areas for muscle attachment, as in all carnivorous theropods. But in other respects ''Tyrannosaurus''’ skull was significantly different from those of large non-tyrannosauroid theropods. It was extremely wide at the rear but had a narrow snout, allowing unusually good [[wikipedia:Binocular vision|binocular vision]].<ref name="Stevens2006Binocular">Stevens, Kent A. 2006, June. ''Binocular vision in theropod dinosaurs'', from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 26, issue 2, pp. 321–330. [http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1256480784253462&url=www.geocities.com/Athens/Bridge/4602/theropod_binocularvision.pdf]</ref><ref name=jaffe>Jaffe, Eric (2006-07-01). Sight for 'Saur Eyes: ''T. rex'' vision was among nature's best, from the Journal of Science , vol. 170, issue 1, page 3. [http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/7500/title/Sight_for_Saur_Eyes_%3Ci%3ET._rex%3Ci%3E_vision_was_among_natures_best]</ref> The skull bones were massive and the [[wikipedia:nasal bone|nasals]] and some other bones were fused, preventing movement between them; but many were pneumatized (contained a "honeycomb" of tiny air spaces) which may have made the bones more flexible as well as lighter. These and other skull-strengthening features are part of the tyrannosaurid trend towards an increasingly powerful bite, which easily surpassed that of all non-tyrannosaurids.<ref name="SnivelyHendersonPhillips2006FusedVaultedNasals">2006, ''Fused and vaulted nasals of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs: Implications for cranial strength and feeding mechanics'', from the Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, vol. 51, issue 3, pp. 435–454. Eric Snively, Donald M. Henderson, and Doug S. Phillips. [http://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app51/app51-435.pdf]</ref><ref name=GEetal96>Erickson, G.M. Van Kirk, S.D.; Su, J.; Levenston, M.E.; Caler, W.E.; and Carter, D.R. 1996. Bite-force estimation for ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' from tooth-marked bones, from the Journal of Nature, vol. 382, pp. 706–708.</ref><ref name=MM03>Meers, M.B., August, 2003. [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tandf/ghbi/2003/00000016/00000001/art00001 Maximum bite force and prey size of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' and their relationships to the inference of feeding behavior,] from the journal of Historical Biology: A Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 16, issue 1, pp. 1–12.</ref> The tip of the upper jaw was U-shaped (most non-tyrannosauroid carnivores had V-shaped upper jaws), which increased the amount of tissue and bone a tyrannosaur could rip out with one bite, although it also increased the stresses on the front teeth.<ref name="holtz1994" /><ref name="paul1988" /> |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:T.rex restoration.jpg|thumb|Life restoration of a ''Tyrannosaurus rex''.]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | The teeth of ''T. rex'' displayed marked [[wikipedia:Heterodont|heterodonty]] (differences in shape).<ref name="Smith2005HeterodontyTRex">Smith, J.B. Heterodonty in ''Tyrannosaurus rex'': implications for the taxonomic and systematic utility of theropod dentitions, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 25, issue 4, pp. 865–887. December, 2005. [http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1256456620451304&url=www.geocities.com/Athens/Bridge/4602/trexteeth.pdf]</ref><ref name="brochu2003">Brochu C.R., 2003. Osteology of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'': insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull, from the journal of Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoirs, vol. 7, pp. 1–138.</ref> The [[Wikipedia:Premaxilla|premaxillary]] teeth at the front of the upper jaw were closely packed, D-shaped in cross-section, had reinforcing ridges on the rear surface, were [[wikipedia:Incisor|incisiform]] (their tips were chisel-like blades) and curved backwards. The D-shaped cross-section, reinforcing ridges and backwards curve reduced the risk that the teeth would snap when ''Tyrannosaurus'' bit and pulled. The remaining teeth were robust, like "lethal bananas" rather than daggers; more widely spaced and also had reinforcing ridges.<ref name="New Scientist1998DinosaurDetectives">''The dinosaur detectives,'' 1998, fromt the Journal of New Scientist. Douglas K, Young S. [http://www.newscientist.com/channel/life/dinosaurs/mg15821305.300] "One palaeontologist memorably described the huge, curved teeth of T. rex as 'lethal bananas'".</ref> Those in the upper jaw were larger than those in all but the rear of the lower jaw. The largest found so far is estimated to have been 30 centimetres (12 in) long including the root when the animal was alive, making it the largest tooth of any carnivorous dinosaur.<ref name=SueFMNH/> |

||

[[Category:Dinosaurs]] |

[[Category:Dinosaurs]] |

||

[[Category:Carnivores]] |

[[Category:Carnivores]] |

||

Revision as of 20:07, 6 April 2017

Tyrannosaurus (pronounced /tɨˌrænəˈsɔːrəs/ or /taɪˌrænoʊˈsɔːrəs/, meaning 'tyrant lizard') is a genus of theropod dinosaur. The famous species Tyrannosaurus rex ('rex' meaning 'king' in Latin), commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture around the world, and is extensively used in scientific television and movies, such as documentaries and Jurassic Park, and in children's series such as The Land Before Time. Tyrannosaurus lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils of T. rex are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the last three million years of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 68 to 65 million years ago; it was among the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist prior to the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event.

Like other tyrannosaurids, Tyrannosaurus was a bipedal carnivore with a massive skull balanced by a long, heavy tail. Relative to the large and powerful hindlimbs, Tyrannosaurus forelimbs were small, though unusually powerful for their size, and bore two primary digits, along with a possible third vestigial digit. Although other theropods rivaled or exceeded T. rex in size, it was the largest known tyrannosaurid and one of the largest known land predators, measuring up to 13 metres (43 ft.) in length,[1] up to 4 metres (13 ft.) tall at the hips,[2] and up to 6.8 metric tonnes (7.5 short tons) in weight.[3] By far the largest carnivore in its environment, T. rex may have been an apex predator, preying upon hadrosaurs and ceratopsians, although some experts have suggested it was primarily a scavenger.

More than 30 specimens of T. rex have been identified, some of which are nearly complete skeletons. Soft tissue and proteins have been reported in at least one of these specimens. The abundance of fossil material has allowed significant research into many aspects of its biology, including life history and biomechanics. The feeding habits, physiology and potential speed of T. rex are a few subjects of debate. Its taxonomy is also controversial, with some scientists considering Tarbosaurus bataar from Asia to represent a second species of Tyrannosaurus and others maintaining Tarbosaurus as a separate genus. Several other genera of North American tyrannosaurids have also been synonymized with Tyrannosaurus.

Description

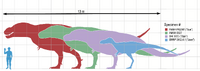

Various specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex with a human for scale.

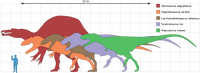

Size comparison of selected giant theropod dinosaurs, with Tyrannosaurus in purple.

Tyrannosaurus rex was one of the largest land carnivores of all time; the largest complete specimen, FMNH PR2081 ("Sue"), measured 12.8 metres (42 ft) long, and was 4.0 metres (13 ft) tall at the hips.[2] Mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from more than 7.2 metric tons (7.9 short tons),[4] to less than 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons),[5][6] with most modern estimates ranging between 5.4 and 6.8 metric tons (6.0 and 7.5 short tons).[7][8][9][3] Although Tyrannosaurus rex was larger than the well known Jurassic theropod Allosaurus, it was slightly smaller than Cretaceous carnivores Spinosaurus and Giganotosaurus.[10][11]

The neck of T. rex formed a natural S-shaped curve like that of other theropods, but was short and muscular to support the massive head. The forelimbs were long thought to bear only two digits, but there is an unpublished report of a third, vestigial digit in one specimen.[12] In contrast the hind limbs were among the longest in proportion to body size of any theropod. The tail was heavy and long, sometimes containing over forty vertebrae, in order to balance the massive head and torso. To compensate for the immense bulk of the animal, many bones throughout the skeleton were hollow, reducing its weight without significant loss of strength.[1]

The largest known T. rex skulls measure up to 5 feet (1.5 m) in length.[13] Large fenestrae (openings) in the skull reduced weight and provided areas for muscle attachment, as in all carnivorous theropods. But in other respects Tyrannosaurus’ skull was significantly different from those of large non-tyrannosauroid theropods. It was extremely wide at the rear but had a narrow snout, allowing unusually good binocular vision.[14][15] The skull bones were massive and the nasals and some other bones were fused, preventing movement between them; but many were pneumatized (contained a "honeycomb" of tiny air spaces) which may have made the bones more flexible as well as lighter. These and other skull-strengthening features are part of the tyrannosaurid trend towards an increasingly powerful bite, which easily surpassed that of all non-tyrannosaurids.[16][17][18] The tip of the upper jaw was U-shaped (most non-tyrannosauroid carnivores had V-shaped upper jaws), which increased the amount of tissue and bone a tyrannosaur could rip out with one bite, although it also increased the stresses on the front teeth.[19][20]

Life restoration of a Tyrannosaurus rex.

The teeth of T. rex displayed marked heterodonty (differences in shape).[21][1] The premaxillary teeth at the front of the upper jaw were closely packed, D-shaped in cross-section, had reinforcing ridges on the rear surface, were incisiform (their tips were chisel-like blades) and curved backwards. The D-shaped cross-section, reinforcing ridges and backwards curve reduced the risk that the teeth would snap when Tyrannosaurus bit and pulled. The remaining teeth were robust, like "lethal bananas" rather than daggers; more widely spaced and also had reinforcing ridges.[22] Those in the upper jaw were larger than those in all but the rear of the lower jaw. The largest found so far is estimated to have been 30 centimetres (12 in) long including the root when the animal was alive, making it the largest tooth of any carnivorous dinosaur.[2]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brochu, Christopher A. and Richard A. Ketcham Osteology of Tyrannosaurus Rex: Insights from a Nearly Complete Skeleton and High-resolution Computed Tomographic Analysis of the Skull. 2003, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, in Northbrook, Illinois. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "brochu2003" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Sue's vital statistics Sue at the Field Museum. Field Museum of Natural History.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Erickson, Gregory M., Makovicky, Peter J.; Currie, Philip J.; Norell, Mark A.; Yerby, Scott A.; & Brochu, Christopher A., 2004. Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs, from the Journal of Nature, vol. 430, issue 7001, pp. 772–775. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ericksonetal2004" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Henderson, DM, 1999. Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing, from the Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 25, issue 1, pp. 88–106 [1].

- ↑ Anderson, JF and Hall-Martin AJ, Russell, Dale A. 1985. Long bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs, from the Journal of Zoology, vol. 207, issue 1, pp. 53–61.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T., 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. New York, Kensington Publishing, ISBN 0-688-04287-2

- ↑ Farlow, James O., Smith MB, & Robinson, JM, 1995. Body mass, bone "strength indicator", and cursorial potential of Tyrannosaurus rex, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 15, issue 4, pp. 713–725. [2]

- ↑ Seebacher, Frank. 2001. A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 21, issue 1, pp. 51–60.

- ↑ Christiansen, Per & Fariña, Richard A., 2004. Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs, from the Journal of Historical Biology, vol. 16, issues 2-4, pp. 85–92.

- ↑ dal Sasso, Cristiano and Maganuco, Simone; Buffetaut, Eric; & Mendez, Marcos A. 2005. New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol. 25, issue 4, pp. 888–896. [3]

- ↑ Calvo, Jorge O., and Rodolfo Coria, 1998, December. New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the as the largest theropod ever found, from the Journal of Gaia Revista de Geociências, vol. 15, pp. 117–122. [4]

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedquinlanetal2007 - ↑ Museum unveils world's largest T-rex skull (2006-04-07) Montana State University.

- ↑ Stevens, Kent A. 2006, June. Binocular vision in theropod dinosaurs, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 26, issue 2, pp. 321–330. [5]

- ↑ Jaffe, Eric (2006-07-01). Sight for 'Saur Eyes: T. rex vision was among nature's best, from the Journal of Science , vol. 170, issue 1, page 3. [6]

- ↑ 2006, Fused and vaulted nasals of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs: Implications for cranial strength and feeding mechanics, from the Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, vol. 51, issue 3, pp. 435–454. Eric Snively, Donald M. Henderson, and Doug S. Phillips. [7]

- ↑ Erickson, G.M. Van Kirk, S.D.; Su, J.; Levenston, M.E.; Caler, W.E.; and Carter, D.R. 1996. Bite-force estimation for Tyrannosaurus rex from tooth-marked bones, from the Journal of Nature, vol. 382, pp. 706–708.

- ↑ Meers, M.B., August, 2003. Maximum bite force and prey size of Tyrannosaurus rex and their relationships to the inference of feeding behavior, from the journal of Historical Biology: A Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 16, issue 1, pp. 1–12.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedholtz1994 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpaul1988 - ↑ Smith, J.B. Heterodonty in Tyrannosaurus rex: implications for the taxonomic and systematic utility of theropod dentitions, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 25, issue 4, pp. 865–887. December, 2005. [8]

- ↑ The dinosaur detectives, 1998, fromt the Journal of New Scientist. Douglas K, Young S. [9] "One palaeontologist memorably described the huge, curved teeth of T. rex as 'lethal bananas'".